The Holy Tongue and the Decapitation of Israel

I believe understanding the historical context of the Talmud deepens its metaphysics.

The Torah imagines a scene worthy of a Hitchcock mystery. A corpse is found between two cities. Who is responsible for it? It tells us, reasonably enough, that the closest city is responsible for it. That city has to perform a ritual to bring the cosmic scales back into balance, by breaking the neck of a calf and throwing it over a cliff.

The Talmud tells us that the pronouncement at the ritual is so solemn that it is one of only eight utterances that have to be said is the holy tongue, Hebrew. [1] The whole list [2] is surprising for what it doesn’t include: the Shema, for instance, or blessings over bread or Shabbat. So why this obscure and arcane ritual?

Talmud goes on to imagine increasingly farfetched scenarios: “What if the corpse is equidistant?” it asks. In doing so, the eglah arufah becomes as mysterious and profound as its more famous cousin, that other slaughtered calf, the Parah Adumah, the Red Heifer. As it does, it hints at why the unclaimed corpse between cities is so vital its ritual must be pronounced in Hebrew.

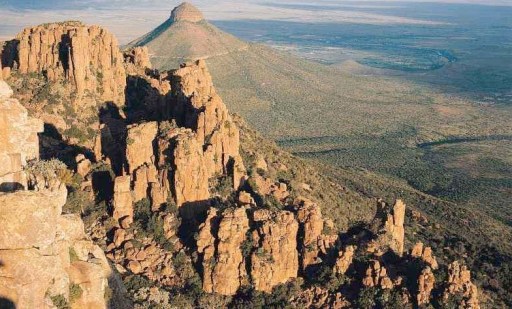

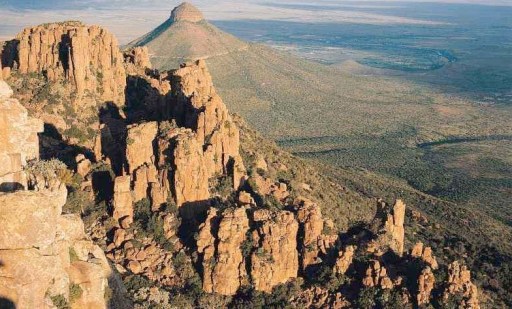

The Mishnah says the Sanhedrin, the assembly of 71 judges in Jerusalem, has to come out to measure which city is closer. Then the elders of that city sacrifice an unblemished calf to rid the world of the unattributed evil. They take it down to a stony ravine, and they break its neck with a hatchet, from behind. Then they declare over this eglah arufah, in Hebrew, they are not responsible for the death of the corpse, or more literally, “This blood is not on our hands,” obviously meaning the blood of the corpse, not the poor calf, which is now on their hands.

The Talmud imagines several scenarios that have increasing unreality:

What happens if two bodies are found exactly on top of each other? Is one body exempt because it is “floating” atop the other? Is the body underneath exempt because it is covered by the body on top? Are both exempt?

What if they are both exactly between the two cities?

What if a body is decapitated and the head and the body are in different places? Do we bring the head to the body, or vice versa?

Dexter or CSI Miami has nothing on the gruesomeness of the debate. The Talmud often considers improbable, even absurd scenarios. A guy with a pole who rushes around a corner and breaks the jug carried by another guy who was rushing from the opposite direction. A dog brings a hot coal in his mouth to ignite a neighbor’s haystack. A goat jumps down from the roof and breaks someone’s utensils. But the empirical unreality of this whole discussion about two corpses found atop each other exactly equidistant from two cities, combined with the seriousness of the crime which presumably is behind it, suggests that there is something deeper at work here.

Gemara asks: If the corpse is decapitated, do we measure to the nearest town from the head or from the body? R. Akiva maintains you measure from the head, specifically the nose, because that is the source of neshama itself. R. Eliezer says measure from the body because the fetus forms from the navel outward – מטיבורו – mi’tiburoh. The Gemarah does not resolve the dispute, nor does Schottenstein, even after conferring with Rashi. Instead, the Mishnah itself concludes:

Rabbi Eliezer ben Yakov says, ‘They measure from the place that he becomes chalal, that is, from his neck.”

Think about that for a moment, and you realize, of course, that this is no resolution at all!

If a body is decapitated, where does the neck go? What is the neck? Anatomically, it may be the series of seven vertebrae C1-C7 connecting the head to the body, but conceptually it is the indeterminate boundary between head and body. When a body is severed at the neck, the neck as such disappears.

So specifying that measurement is to be taken from the neck of a decapitated body defers but doesn’t resolve the problem. The neck disappears into the same limbo or indeterminate space between as does the guilt of the murderer, which now threatens to taint both of the nearest cities. The necks of the calf and the corpse are not the only things that are broken.

Throughout the Talmud, there are several passages where the rabbis cannot reach a conclusion. And there are also other passages when the conclusion is to invoke a chok or a commandment that defies rational explanation, a transcendent mystery we’re supposed to obey without understanding. Like the attempt to decipher the parah adumah, the sages here seem to let the physics of the matter dissipate into metaphysics. And yet, if we view this part of Sotah as having literary coherence, it reveals what the rabbis may have had in mind and helps us penetrate the mystery.

When the Mishnah calls out the ritual, it doesn’t say “the ritual to expiate the guilt of an unclaimed corpse,” which would be both more dramatic and make more sense, but eglah arufah, the calf that has its neck broken.

Second, the Gemara goes into careful detail about a corpse that is decapitated. A corpse has special status and its own name (“korbah”) if it is strangled by the neck and is different from a corpse slain by an instrument like a hatchet, in which case it is a “chalal.” (There’s a great one-liner in here. The Gemarah sees fit to tell us that, “If a corpse is still writhing [because it was insufficiently strangled] it is not yet a corpse.”)

Third, the Mishnah then details exactly how the neck of the calf is to be broken: it is to be decapitated with a cleaver to the back of its neck. In other words, the calf is like the imaginary corpse they were just so concerned with that has been killed at the neck.

Fourth, where is to this be performed? One would think that it would be precisely where the body was found, but rather the Mishnah prescribes it to be done in a desolated valley or a river, a wasteland, a no-man’s land. Further, Rashi explicitly says this must be land that has never been planted and is unsuitable for planting or working, and after the rite of eglah arufah is performed, the land is never again to be worked. The immediate symbolism is clear: just as the the unknown murderer, the real no-man, disappeared into the twilight zone, the expiation is directed there, too. We recall, perhaps, the second of the Yom Kippur sacrifices, the scapegoat sent into the wilderness for our sins.

There are may other mysteries worthy to be called out here. For instance, with the inevitable logic of rituals, the calf, too, must be one that has never been worked in yoke, invoking again, the neck … but I’ll skip over these to drive to what I believe is the heart of the matter. Why does the neck, forgive me, bear so much weight here?

The Lubavitcher Rebbe comments on “the neck.” He calls it “the precarious joint” :

In the Torah, the neck is a common metaphor for the Holy Temple… The Sanctuaries are links between heaven and earth, points of contact between the Creator and His creation. … G-d, who transcends the finite, transcends the infinite as well, and He chose to designate a physical site and structure as the seat of His manifest presence in the world and the focal point of man’s service of his Creator….

The Sanctuary, then, is the “neck” of the world … the juncture that connects its body to its head. the neck that joins the head to the body and channels the flow of consciousness and vitality from the one to the other: the head leads the body via the neck. …

… The Sanctuary’s destruction, whether on the cosmic or the individual level, is the breakdown of the juncture between head and body — between Creator and creation, between soul and physical self. Indeed, the two are intertwined. When the Holy Temple stood in Jerusalem and openly served as the spiritual nerve center of the universe, this obviously enhanced the bond between body and soul in every individual….

from “The Neck” chabad.org/parshah/article_cdo/aid/3222/jewish/The-Neck.htm

The intensity of care taken by the rabbis to assign responsibility for unclaimed corpses, and presumably unsolved murders, to this or that town increases even more so in the Diaspora (the galus), when there is no Sanhedrin and no Temple in Jerusalem. This impossible hypothetical, and the seriousness with which the Rabbis debate its halachah, seems to be as much about a lamentation of the Destruction of the Temple in 70 CE and the Jews’ exile to a dispiriting, liminal, desolate, precarious realm. We inhabit a “no-man’s land” where law and order has broken down and corpses are piling up, and bodies are stuck equidistant between cities so that there is no clear authority. We’re stranded between two Houses of Judgment, not just two cities, but two order of preserving the Jewish religion and two orders of being, the Temple with its ritual, and the Talmud, with its exegesis and elaboration. Assigning responsibility becomes impossible.

The end of Sotah depicts an apocalyptic scenario of the breakdown of all law and order, a recounting of the terrible things that occur when there are so many unsolved murders that the rite of eglah arufah has to be abandoned and there so many adulteresses that the ritual of Sotah ceases.

WHEN [THE SECOND] TEMPLE WAS DESTROYED, SCHOLAR AND NOBLEMEN WERE ASHAMED AND COVERED THEIR HEAD,MEN OF DEED WERE DISREGARDED, AND MEN OF ARM AND MEN OF TONGUE GREW POWERFUL. NOBODY ENQUIRES, NOBODY PRAYS AND NOBODY ASKS.UPON WHOM IS IT FOR US TO RELY? UPON OUR FATHER WHO IS IN HEAVEN … THE COMMON PEOPLE BECAME MORE AND MORE DEBASED … IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE MESSIAH INSOLENCE WILL INCREASE AND HONOUR DWINDLE; … THE MEETING-PLACE [OF SCHOLARS] WILL BE BROTHELS… AND THE DWELLERS ON THE FRONTIER WILL GO ABOUT [BEGGING] FROM PLACE TO PLACE WITHOUT ANYONE TO TAKE PITY ON THEM; THE WISDOM OF THE LEARNED WILL DEGENERATE, FEARERS OF SIN WILL BE DESPISED, AND THE TRUTH WILL BE LACKING; … A MAN’S ENEMIES WILL BE THE MEMBERS OF HIS HOUSEHOLD; THE FACE OF THE GENERATION WILL BE LIKE THE FACE OF A DOG, A SON WILL NOT FEEL ASHAMED BEFORE HIS FATHER. SO UPON WHOM IS IT FOR US TO RELY?

– Sotah 49a-b

This is just a small section of the Yeridas HaDoros, the Decline of the Generations, a work of vast Rabbinic imagination and mourning.

I believe the historical context for this apocalyptic vision doesn’t explain away but rather deepens the Talmud’s metaphysical intensity. Knowing that this is a lamentation for the Temple helps us understand the entwinement of Hebrew as holy tongue with the Temple with the spiritual health of Israel. Speaking and reading Lashon HaKodesh is meant to recall that broken entwinement, to bridge over the fissures, to heal or prevent the ruptures at the core of functioning society itself by connecting the bloody and mundane, the hard valley of the wasteland, to the world to come, olam habah.

Israel is the calf whose neck has been broken. Israel is the floating corpse unclaimed between two cities. In a time of calamity and the breakdown of social order, even the ritual itself is to be abandoned, as is the ritual of sotah.

If we read Sotah correctly, we are being admonished that the only thing that will put our head on our shoulders, that will connect the soul to the body of Israel, is to preserve Hebrew, especially to be recited in these moments of rupture and decapitation.

Palo Alto

Shavuos 5774

NOTES:

In honor of my classmates, Boris Feldman, Joseph Joffe, and Sam Tramiel, and my teacher Rabbi Yitzchak Feldman –

[1] Sotah 45

[2] The eight utterances that must be said in Hebrew are:

- THE DECLARATION MADE AT THE OFFERING OF THE FIRST FRUITS during Shavuos

- THE FORMULA OF CHALIZAH [renunciation of a Levirite marriage] releasing a woman to be able to wed again if her husband dies and she is childless

- THE BLESSINGS AND CURSES to be pronounced from two mountaintops when the Jews cross the Jordan and were united with the land of Israel

- THE PRIESTLY BENEDICTION All the Kohanim are commanded to bless Israel on Yom Kippur

- THE BENEDICTION OF THE HIGH PRIEST on Yom Kippur, upon finishing reading of the Torah

- THE SECTION OF THE KING, The “HaKahal” (assembly): Every seven years the King assembles everyone in Courtyard and recites from Deuteronomy … “and One who hears it and doesn’t understand Hebrew must still stand in awe as if receiving Torah at Sinai.”

- THE SECTION OF THE CALF WHOSE NECK IS BROKEN when corpses are found between cities

- THE ADDRESS TO THE PEOPLE BY THE PRIEST ANOINTED [TO ACCOMPANY THE ARMY] IN BATTLE.

“Towards the end of parsha Noah we read the story of the Tower of Babel. We are told: וַיְהִי כָל הָאָרֶץ שָׂפָה אֶחָת וּדְבָרִים אֲחָדִים, “The whole earth was of one language…”. (Gen 11,1) Rashi comments that the language was Hebrew.

Midrash Rabbah (Lev. 32,5) says that a virtue our ancestors had in Egypt and one of the causes for their redemption, was “they didn‘t change their tongue.”

In 1913, the “Language War” erupted in Palestine after word leaked out that the German Hilfsverein (Ezra) Organization was planning to make German the language of instruction in its Technion Institute in Haifa. A rebellion of students and teachers successfully imposed Hebrew as the language of instruction.

I think it was David Bar-Ilan, former editor of the Jerusalem Post who said about the miracle of Hebrew being resurrected as the living tongue of Israel, “King David would be more comfortable speaking Hebrew on the streets of Jerusalem than Shakespeare speaking English on the streets of London.”

Twitter, Email or Print this blog:

You must be logged in to post a comment.